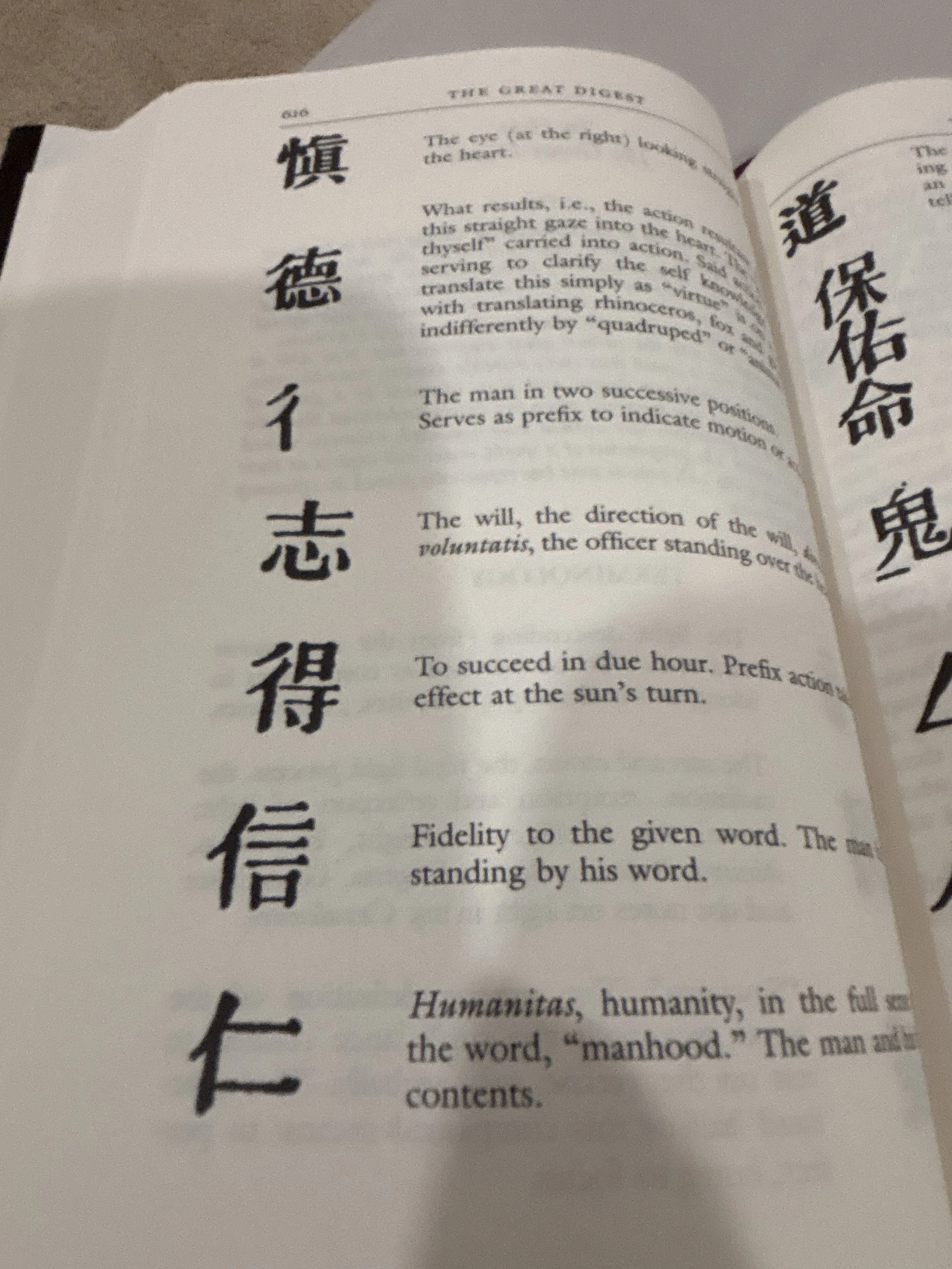

The apex of the pantheon to be traversed by way of a well-lit path, lamp in hand, mirror held out at arms length in lieu of a compass

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French wine glass and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between Sophocles and Shakespeare, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of the imagination.

G Davenport

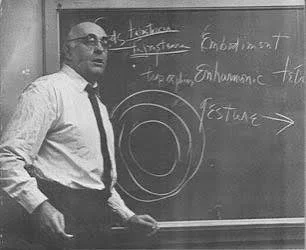

One word for every week of the year. A completely tantalizing entry point into a dazzling intellect, deployed with so much playful and exuberant generosity as to make almost every other essayist of note seem arid and bereft by comparison. He could decode the cantos or the Maximus. He could tell an anecdote that was topical and somehow timeless. He could make you see what he saw by looking closely and encourage the belief that there was always an even more perspicacious vantage and always something more worth finding.

Not rah rah enthusiasm but inspiring all the same.

I liked him on Thoreau, on Wittgenstein, on any number of Greeks whose strangeness he conveyed, and so much else that made me feel paltry-minded and palsied. Here he is on the tall, raving scrivener of Maximus:

His poetry is inarticulate. His lectures achieved depths of incoherence. His long poem Maximus was left unfinished, like most of his projects and practically all of his sentences. He put food in his pockets at dinner parties. He was saved from starving by Hermann Broch. He once ate an oil rag. He was, like Coleridge, a passionate talker for whom whole days and nights were too brief a time to exhaust a subject. He wrote a study of American musical comedies, was a professional dancer, served in the State Department under Roosevelt, went to the rain forests of Yucatan, was rector of a college. He was taller than doors and had the physique of a bear. He was an addict as he grew older to both alcohol and drugs.

Carson indicates that she “wants to be unbearable,” but in a metaphysical sense, and part of me wants to sit with that and think about until the brain pan overheats and unkinks itself and part of me wants to just listen to her readings of other writings, her explications and probing, the ruminative mood captured in unspooling connections and juxtapositions. I care more for the fate of scalded tomcats than I do for her volcano paintings, except to the extent they place her into contact with that animating declaratory intelligence, its colloquial verve, the kooky violence with which it puts the learned next to the bodies of knowledge and desiring drives.

GD in his introduction to the glass essay provided a door and who knows where the path might wind once you took a step off into her poetry and went a-voyaging and if you ever were to find your way back to take a deep breath, you might go back to see if there were another door, to Iceland or Denmark or Joyce and Balthus, wanting to have the same highly calibrated powers of observation trained on something new about which you know little and so go to GD, on whom next to nothing is lost.

It seems like most people ask: how can i throw my life away in the least unhappy way possible? SB, of whole earth fame